God Has a Name by John Mark Comer: Summary & Notes

The English word 'God' is not a common denominator.

When two people talk about God, they're rarely thinking of the same thing because the English word 'God' is not a common denominator. As humans, we tend to make God in our image instead of the other way around. The God we know confirms our beliefs, votes for who we vote for, and agrees with us on everything. Therefore, your response to the question, "Who is God?" may be the most revealing thing about you.

Who does God say he is?

If we want to understand who God is, there's no better place to look than his word. In God Has a Name, Pastor John Mark Comer breaks down, line by line, one of the most quoted Bible verses in the Bible by the Bible: Exodus 34: 6-7. These lines are God telling us what he is like in his own words.

So Moses chiseled out two stone tablets like the first ones and went up Mount Sinai early in the morning, as the LORD [Yahweh] had commanded him; and he carried the two stone tablets in his hands. Then the LORD [Yahweh] came down in the cloud and stood there with him and proclaimed his name, the LORD [Yahweh]. And he passed in front of Moses, proclaiming, “The LORD [Yahweh], the LORD [Yahweh], the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, maintaining love to thousands, and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin. Yet he does not leave the guilty unpunished; he punishes the children and their children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation.

Notice, when God reveals himself to us, he doesn't start with how powerful or mighty or omnipotent he is. He starts with his name.

In the time period and language that this passage was written, a person's name wasn't just a label like "Bob" or "Suzanne." It was the very essence of a being--the destiny, identity, and nature of a person. God tells us his name, then describes his character.

Why it matters how you see God

Following God is a constant journey of unlearning who we think he is to find out who he actually is. The Bible is constantly prodding and encouraging us to see God more accurately--to know who he truly is and not just what we've been told about him.

How we see God is important for two reasons:

First, how you think about God shapes the way you relate to him, and since how we relate is how we relate, it also shapes how you relate to people. If you feel constantly judged and condemned by God, that will likely be your baseline emotion toward the people in your life. If you feel accepted and loved by him, you'll likely treat others with the same acceptance and love.

The way you relate to the people closest to you is a good indication of how you relate to God. Are your relationships filled with criticism, judgment, and avoidance? Or are they filled with intimacy, trust, and acceptance? Either way, it likely mirrors your relationship with God.

Second, we become like what we worship. In the Bible, you'll often read stories of people making animal sacrifices to God. We're not as far removed from this tradition as you would think. In the ancient world, animals were a form of currency.

Today, most of us don't kill animals on an alter. Instead, we sacrifice money, time, family, morals, or whatever else it takes to get what we think we want out of life. If you don't know what you worship, look at what you sacrifice for. Worship isn't just singing songs at a church service. It's the shaping of our lives around another entity. It's sacrificing one thing in service of whatever is more important to us. We all worship because we all make sacrifices. Humans can't stop worshiping any more than we can stop breathing.

Whatever we choose to worship informs our priorities and consequently makes us who we are.

Who is God?

Now that we know why our view of God is important, we can dive into how he describes himself and what that means for us. In his book, Comer breaks down Exodus 34 (quoted above) one line at a time. Through these verses, we'll learn God is compassionate, gracious, and slow to anger. He does get angry, but his fuse is unfathomably long.

Merciful

In the Old Testament, word order matters. It signals importance. The first thing God says about himself is that he's the "compassionate and gracious God." He doesn't start with power or might because those aren't the attributes he thinks are most important for you to know about him. He starts with compassion. He starts with grace.

God's baseline emotion toward you isn't condemnation, judgement, or anger. It's mercy. He's not out to get you. He's not looking to punish you. He's eager to forgive and wants you to come running back. "When it comes to mercy, you don’t have to twist God’s arm," and "the only thing that can effectively keep you from God’s mercy is thinking you deserve it."

The thing is, God shows mercy to all, including those we would consider our enemies. We want him to show mercy to us and justice to everyone else, but God doesn't play favorites when it comes to grace. Yahweh is constantly looking to bless us so we can bless the world, but it's only when we let him be the judge that we can finally "let go of our heart's warped lust for revenge." He sets us free so that we may set others free.

Slow to Anger

God's anger has always been his one attribute that has confused me most. I suspect many others feel the same way.

There seem to be two common ways of thinking about God's anger:

- God is a gentle, ever-patient god who never get's angry or

- God's default feeling towards humanity is anger. We're all going to burn in hell because of his wrath.

Neither is right. God does get mad, but it's not his baseline emotion toward you because he's slow to anger. Remember, order matters; God mentions mercy and compassion before even mentioning anger. He describes himself as "the compassionate and gracious God," and only then does he mention that he's "slow to anger." In other words, "you can make God mad, but you really have to work at it."

Because God's anger is such a big topic, I'll explore it further in a later section.

Personal

God is a person in the sense that he's a relational being. He's not a doctrine, theological system, or impersonal force hiding in the clouds. He's a God who wants to know you and to be known by you. In short, he wants a relationship with his people. Like people, he has feelings. He feels pain and anguish and joy and love.

Consistent

God is true to his character. Unlike with humans, there are no true colors to discover "once you get to know him." He is who he is all the time. There's no façade, no mask, and no "gotchas." Whatever he's like is how he always was and will be like. Thus, "if God is compassionate, he is compassionate all the time."

Responsive

Because God is a 'person,' he responds. He's not an indifferent deity floating off in the distance. He doesn't run away when things get messy; he runs toward the mess. He's involved, alive, and responsive to the humans he's created. There are several stories in the Bible where a human being talks God out of doing something. He changes his mind. He can be convinced and influenced and moved.

He isn't merely tolerant of, but actually open to our ideas. He's not an immovable robot with a "what’s-going-to-happen-is-going-to-happen-with-or-without-me" kind of attitude. This dynamic God is "more of a friend than a formula."

Wrath

Remember when I said I'd talk more about God's anger later? It's later.

Why is Jesus flipping tables?

One story from the Bible that helped me better understand God's anger is when Jesus seems to go berserk in a temple. He walks into the temple one day and see's people trading and using his father's house as a marketplace. In a rage, he flips over their tables and screams at all the money changers, chasing them out of the temple.

I've read that story a dozen times, and every time it felt at odds with what I thought God was supposed to be like. After all, isn't he supposed to be slow to anger?

Upon further inspection, I realized Jesus' actions were not spur of the moment. He didn't just walk into the temple one day and suddenly let his emotions get the best of him. No--this was a long time coming because Jesus had been going to the temple since he was a boy. He grew up seeing these same people disrespect this place of worship for years. What he saw wasn't a surprise to him. It wasn't just that Jesus one day lost his cool. This was a purposeful, deliberate anger--a slow build up to him finally saying, "ENOUGH!"

Jesus' actions felt so out of character because that's the point. When God finally does let out his anger, you know it's for a reason. It's never "all of a sudden." It's deliberate, on purpose, and the right response at the right time to the situation. When God get's angry, it's a reckoning.

Us vs. Him

Another way to better understand God's anger is to compare it to ours:

Our Anger | God's Anger |

usually from wounded pride / ego | stems from a parent-like love for his children |

inherently selfish | protective of his people |

disproportionate to the offense | the punishment fits the crime |

quick to flare up | on tempo, patiently building up to the right moment |

God the Father

I came from a relatively conservative Christian background and grew up thinking God was constantly angry with me because I sinned. I felt that unless I got my act together, God's wrath would consume me in a fiery blaze. It led to shame, hiding, and guilt, and I could never seem to reconcile this God with grace.

Now, I'm starting to see the err in my perspective. It's not that he's always angry at me. Remember, God's baseline emotion toward humanity isn't wrath, but mercy--not disappointment, but compassion. Any anger he does show is born out of a parent-like love for his children.

Imagine you have a young daughter who gets raped. You will rightly be blindingly livid. You should be. It's the correct response. Your wrath wasn't borne out of evil, but out of love for your daughter.

God does get angry, but he get's angry when it's the emotionally mature and correct response to a situation. And like any good Father, he's not eager to catch his child red-handed but will discipline her if he does because he wants to expel all evil from her life.

God is merciful, but that doesn't mean he will ignore your sin. On the contrary, because you're his child, he'll deal with it even more seriously. A father will discipline his children much more harshly than other peoples' kids because he cares how his kid turns out. When a dad looks at a child who isn't his, he's not all that concerned about who that kid becomes because he doesn't love someone else's child.

Punishment and Discipline

I think many of us have a vision of a tyrannical God who is looking for opportunities to punish us. After all, some of the stories in the Bible depict God doling out some pretty harsh punishment.

In some stories, God does step in to punish his people, but that's seldom the case. Typically, he doesn't need to step in to discipline humanity because he knows sin, in many ways, comes with its own punishment. When God takes his protective hand off of us and lets us experience the full tangible consequence of our sin, that's called his passive wrath.

Sin already comes with cruel, unforgiving, merciless consequences. We're capable of ruining our lives without him ever intervening. Sometimes he steps back and lets us have our way so we can realize his is better.

"Sin" is it's own punishment and "righteousness" it's own reward.

If you lie enough times, you'll spin yourself in a such a twisted web of reality that you don't know what's even true anymore. If you lust outside of your marriage, you'll be constantly dissatisfied with your spouse and on edge about everything. If you steal without getting caught, you'll be constantly paranoid.

In other words, "Yahweh is forgiving, but sin is not."

God's love is an attribute but wrath isn't because his wrath is born out of his love. His wrath is his righteous response to evil in the world coming from a place of protective love. The verse is God is love, not God is wrath.

Jesus

We can't talk about the character of God without talking about his human form, Jesus.

Christus Victor

I was often taught about Jesus as he fit into the metaphor of substitutionary atonement, which essentially means that Jesus was crucified so we may be made right with God. While this metaphor isn't wrong, it wasn't the dominant metaphor in the eyes of the scripture writers. That title belongs to Christus Victor meaning "Christ is Victorious."

You can feel a tension in God's character throughout the Bible--between justice and mercy, grace and wrath. Throughout the Old Testament, we're led through story after story wondering how God is finally going to resolve this tension.

"And the resolution finally comes, not in a brilliant lecture by a well-known theologian, but in a rabbi from Nazareth named Jesus." Jesus is the resolution between mercy and justice--the ultimate expression of God's character. God's very nature is to be merciful and gracious, but also to reign justly over evil, and in Jesus, this tension we've felt throughout the Bible is finally resolved.

Christus Victor is the idea that God has been waging war against the evil spiritual powers for thousands of years, and the cross is God's "decisive blow in his campaign against evil." The whole climax of the Bible isn't just that Jesus came to take the penalty of our sin, but that Jesus died on the cross to completely overcome all evil. "On the cross, Jesus defeated Satan, his pantheon of wild and dangerous beings, and even death itself."

"Jesus takes all our failure—millennia of broken promises—and he drags it to the cross, absorbing it in his death and then breaking its hold over humanity through his resurrection."

Misconceptions

There are more than a few misconceptions about Jesus, but there are two that Comer addressed which stuck out to me.

First, Jesus wasn't a newcomer to God's story. He's been there since the beginning, working with God the Father in their war against evil. Second, Jesus wasn't merely an unfortunate victim of his father's anger issues. He wasn't forced to accept abuse to keep dad from exploding. Again, he and God the Father were working in tandem to break evil's hold on humanity. "[Jesus'] resurrection breaks the spine of death itself, not through violence, but through sacrificial love." He was the long-awaited resolution to the tension that ached in the bones in humanity for a just and merciful ruler.

Through Jesus, we're given the absolute example of who God is in the flesh. As humans, we're far from the perfect man Jesus was, but we follow him one day at a time, one step at a time, to slowly close the gap between who we are and who he is.

The Bible and the Times

If we're to understand the messages in the Bible, it's important to understand the societal backdrop over which it was written and how that differs from today.

Creation

Compared to other creation myths, the Bible offers a story that was radically out of step with its time. Most ancient creation myths claim the universe was borne out of violence, and the galaxies were the result of a cosmic collision between jealous, territorial gods. The Bible offers a different story. One where the world was born not out of conflict, or war, but out of God's overflowing creativity and love.

The Problem of Evil

A great source of doubt for many people, including myself, is the problem of evil: how could a god who claims to be merciful, kind, and loving allow so much evil to flourish in the world.

How does one reconcile a compassionate and gracious God with all the horrific acts we see on the news and even in our everyday lives?

Weirdly enough, the Bible--the text you would think should have the most to say on this subject--doesn't really talk about The Problem of Evil. The scripture writers don't talk about it because in their time, evil was assumed.

Jesus prayed, "Your Kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven." The assumption in this prayer is that God's will was not already done on Earth. On Earth, other "wills" are at play. The scriptures writers were living in an era where the prevailing view was that there are other real spiritual beings with agendas and wills of their own operating on Earth. Of course there's evil; planet Earth is a spiritual battlefield. One where we fight not with weapons, but with prayer and sacrificial love.

But wait... isn't God supposed to be the all-powerful one true God? How can there be other forces, gods even? Comer explains that it comes down to love:

"it’s not that God’s will is weak—on an even playing field with all the other wills. As if we, God, and Satan are all equal players in a game for the world. It’s that in the universe God has chosen to actualize, love is the highest value, and love demands a choice, and a choice demands freedom. So God has chosen to limit his overwhelming capacity to override any “will” stacked against him, in order to create space for real, genuine freedom for his creatures, human and nonhuman."

The Problem of Evil has credence in today's society because we don't acknowledge other real evil forces in the world. By dismissing the existence of the devil, we've attributed his evil to God.

"The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he doesn’t exist.” - Keyser Söze

Thus, "when our worldview became shaped more by secularism than by Scripture, we created a philosophical problem with no good solution."

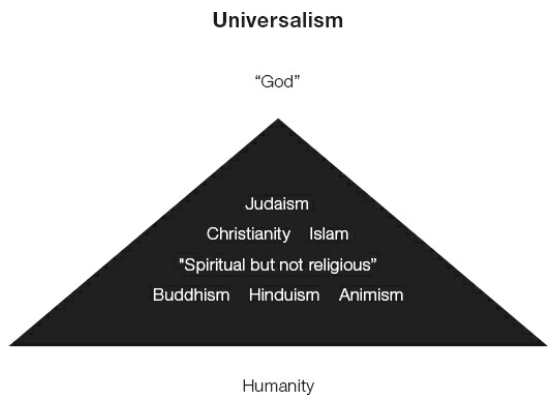

Universalism vs. Monotheism

Society's current dominant perspective on religion is universalism, which is essentially the idea that "all paths lead up the same mountain," all religions basically say the same thing, and we're all basically worshipping the same God. Here's what the idea of universalism looks like as a diagram:

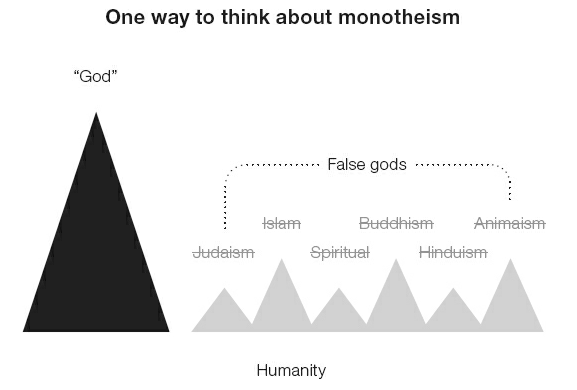

Unfortunately, Jesus did not see the world through the lens of universalism. He was much more in line with the worldview of monotheism. That said, his definition of monotheism may not exactly match what immediately comes to mind for most of us. Our current culture's idea of monotheism often looks like the next image where there's only one true God at the top of the superior mountain and the rest are false gods atop false mountains. However, that may not be the most accurate way to look at it.

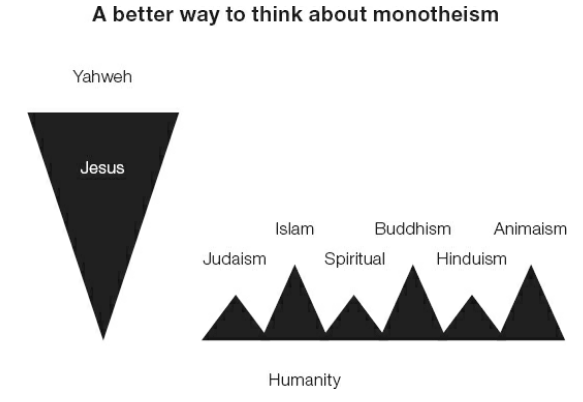

It's not that the scripture writers were trying to denounce false gods. They weren't claiming the other mountains didn't exist and that if you follow the gods atop them you won't see results in your life. You can climb other mountains. You can change your life following other doctrines. Whether or not other gods exist wasn't the primary concern. It's that capital 'G' God's way flips the whole model on it's head more like this next image.

John Mark says it best: "It’s not so much that 'Jesus is the only way to God.' I mean, he is, but a better way to say it is: Jesus is God come to us."

As humans, we could never climb high enough up a mountain through works to get to God. Instead, God wrapped his love in flesh and sent his only son to be crucified so that he may come down and dwell with us.

Closing Thoughts

I've heard the following sentence many times (out of my mouth and others): "I couldn't believe in a God who____." This line makes an inherent claim that what we think or feel about God "is an accurate barometer for what he is actually like." While reading this book, I've come to understand how much my barometer needed recalibrating.

Like any good book, this one has forced me to confront the ways in which I've been blindly following dogma, and it's released me from a lot of the unhealthy ways I've seen God.

One idea that made a huge impact on me is that we only relate one way. For the longest time, I couldn't understand why I was so judgmental toward people, especially those closest to me. I had impossibly high standards, snapped quickly, and was easily disappointed (i.e. the opposite of merciful). Reading and reflecting on this book made me realize that's how I was relating to God. I always felt like he was looking down on me with a judgmental eye--constantly holding me to an impossible standard. I realized how that view made me shrivel up in shame and turn away from him. That's certainly not how I want my closest family and friends to relate to me, and I don't think that's how God ever intended for me to relate to him. Say it with me, God's baseline emotion toward you is mercy.

I hope this summary helped you see God in a new, truer, better way.

Footnotes

You'll notice I interspersed several direct quotes throughout the summary where I couldn't possibly think of a better way to explain an idea than Comer. Unless otherwise stated, any quotes are directly from God Has a Name by John Mark Comer.

Although I did my best to accurately represent the ideas presented in God Has a Name, I inevitably may have committed some errors. Any misinterpretations or inaccuracies in this summary are mine.